By Jan Resseger

January 23, 2014 - 11:57 am CST

Before and After. New Orleans has a new timeline. A new zero point. However, a natural event is by no means the sole cause for our new era. To understand post-Katrina, you have to understand pre-Katrina. Many folks in post-Katrina New Orleans, particularly in terms of public education, don’t follow this simple pre- and post-postulate. They are salivating to start from scratch, to establish a new day and a new order, with nothing but disdain for the prezero… In New Orleans we do have a new moment. But it is not a moment out of time. And it is not a story that only those in power will tell… The before and the after. The respect for elders and ancestors and cultural traditions. Without this full picture, our public education, our culture, our souls cannot continue to grow. Without imparting the knowledge of and action in history and struggle, we cannot teach our children well.” —Jim Randels and Kalamu ya Salaam, teachers at Students at the Center, a student writing program at New Orleans’ Frederick Douglass High School and Eleanor McMain Secondary School. (Kristen Buras, Jim Randels, Kalamu Ya Salaam and Students at the Center, Pedagogy, Policy, and the Privatized City: Stories of Dispossession and Defiance from New Orleans, [New York: Teachers College Press, 2010], p. 15)

Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in early September of 2005. The story of what happened to public education in that city after the hurricane remains highly contested.

The Scott Cowen Institute at Tulane continues to publish data said to prove the schools—now well over 80 percent privately managed charters—have been transformed.

Mercedes Schneider, a Louisiana public school teacher and statistician, blogs regularly about how the numbers are being slanted to paint the charterization as an improvement. Research on Reforms conducts similar research.

In the summer of 2006, researcher Leigh Dingerson described the devastation in Dismantling a Community. And in 2010, the Institute on Race and Poverty at the University of Minnesota Law School concluded: “The ‘tiered’ system of public schools in the city of New Orleans sorts white students and a relatively small share of students of color into selective schools in the OPSB (Orleans Parish School Board) and BESE (Louisiana Board for Elementary and Secondary Education) sectors, while steering the majority of low-income students of color to high-poverty schools in the RSD (Recovery School District) sector… As a result of rules that put RSD traditional schools at a competitive disadvantage, schools in this sector are reduced to ‘schools of last resort.’”

Naomi Klein describes the charter school experiment in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina as the defining example of what she calls “disaster capitalism”: “New Orleans was now, according to the New York Times, ‘the nation’s preeminent laboratory for the widespread use of charter schools’…. I call these orchestrated raids on the public sphere in the wake of catastrophic events, combined with the treatment of disasters as exciting market opportunities, ‘disaster capitalism.’” (The Shock Doctrine, pp. 5-6)

My own week-long visit to New Orleans in July of 2006 forced me to see realities I had previously been too naive to understand. The physical wreckage remained in many parts of the city, but more troubling were the stories I heard from former teachers, parents, attorneys, church leaders and parent advocates in a series of conversations I had arranged in coffee shops and sometimes in people’s homes. The stories were about a long history of white power and privilege and black dispossession, a history, according to many with whom I spoke, reproduced in the ten months since Hurricane Katrina had struck. I describe my visit to New Orleans here. I already knew about the $24 million in seed money (followed by other huge grants) from then U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings and additional funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to support the mass charterization of the city’s schools. But during my visit to the city, I listened to those on whom the New Orleans school experiment was being imposed.

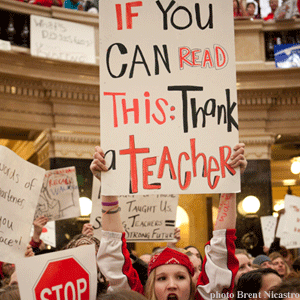

Fast forward to mid-January, 2014, eight years after the Louisiana’s legislature expanded the state Recovery School District to encompass the majority of New Orleans’ public schools, the Orleans Parish School Board fired all 7,000 of New Orleans’ teachers and the experiment began. Last week the Times-Picayune reported that an appeals court has upheld an earlier decision of a trial court that the Orleans Parish School Board wrongly terminated the district’s teaching staff who were denied due process and were not considered for rehiring as the new school experiment took place. The decision promises a financial settlement for all teachers who held tenure at the time they were summarily dismissed.

The case will surely be appealed again, and no one knows how the Orleans Parish School Board—left with only six schools after 2005-2006 when the rest were deemed “under-performing” and seized by the Recovery School District—could possibly pay the damages, which are expected to add up to $1.5 billion. The appeals court makes the state responsible for only a small portion of the damages. The appellate judges declare that tenured teachers should have been given priority when positions opened in the Recovery School District. Instead positions were advertised nationally followed by vastly expanded hiring of new college graduates coming out of alternative certification programs.

The Times-Picayune reporter comments: “The decision validates the anger felt by former teachers who lost their jobs. It says they should have been given top consideration for jobs in the new education system that emerged in New Orleans in the years after the storm. Beyond the individual employees who were put out, the mass layoff has been a lingering source of pain for those who say the school system jobs were an important component in maintaining the city’s black middle class. New Orleans’ teaching force has changed noticeably since then. More young, white teachers have come from outside through groups such as Teach for America… Though many schools have made a conscious effort to hire pre-Katrina teachers and New Orleans natives, eight years later, people still come to public meetings charging that outside teachers don’t understand the local students’ culture.”

The lesson I have personally learned during eight years of watching the vast experiment with New Orleans’ schools is that power and money can undermine institutions I believe should remain democratically governed, publicly regulated, free, universally available, and designed with a civic purpose. I am relieved at least to see the appeals court affirm that public institutions are bound by the contracts they sign with their employees. I hope a higher court will affirm this decision.

For more go to: http://janresseger.wordpress.com/